No doubt all readers have been waiting impatiently for this blog’s first mention of Hildegard von Bingen, the Rhineland Abbess famous as an ‘early female composer’. She was not, of course, only or even primarily a composer, but a poet, mystic, theologian, leader, and fierce advocate for what she saw as righteousness and justice. As the convener of a community, however – and that is as good an understanding of the Magistra of a convent as any – it is clear that her music played a role in the spiritual life of her abbey.

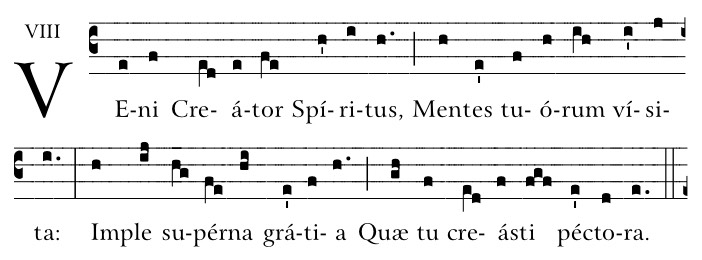

As one would expect of music of the time (twelfth century) it is monodic – a single melodic line for (probably) unaccompanied voices. Less expected, however, is a level of complexity: specifically, some of the ways in which music was made memorable are subverted by her innovations. The work we are looking at today, a sequence hymn called columba aspexit for the celebration of one St Maximinus, for example, undermines the expected ‘form’ of a sequence hymn, by having the pairs of lines an inexact rather than a fairly rigorous repetition.

The text set in the hymn gives a mystical image of the honoured Saint as he celebrated Mass, using multisensory imagery drawn from several biblical texts. The dove – evoking the Holy Spirit – looks in through the window of Christ’s mercy; the celebrant’s face exudes a balm; the sun of God’s love burns hot; the temple is constructed from cedar and cypress with jewels; a deer ruches to a fountain of clear water; a ram is sacrificed on a mountain; wisdom personified has nursed the builder who rises with eagle’s wings.

The music in its turn seems to reflect the swirling of incense entwining itself around the church and infusing the prayers of the faithful into the ritual action depicted. Musicologist Richard Taruskin describes ‘a lyricism of mystical immediacy’.

Despite myself being known to have been reduced to tears by a simple line of plainchant, one reflection I often have on medieval vocal music is that the intended ‘audience’ is often the singers themselves, rather than a congregation who themselves remain passive, or even a Divinity observing from above. No doubt as liturgical music (the sequence hymn comes between an Alleluia and a Gradual during the Mass) it partakes in the constant hymn of heavenly praise, but it is conversion and contemplation for those singing it that seems to be the primary purpose and effect of the music.

Does that mean, however, that it does not make a theological claim? μὴ γένοιτο! How can music that itself forms and participates in an act of worship not reveal to the contemplative heart more of the nature of the object of that worship. Theology is made material in Liturgy just as Godself is made present in Sacrament.

Leave a comment