It would be inconceivable that this blog finishes with the music of Messiaen, but I do assure those of you who have stuck through my posts for the last few weeks that next week will feature music by a different composer. While doing Messiaen season, however, it would seem remiss for a post on the eve of Corpus Christi not to concern itself with his motet O sacrum convivium. The text, attributed to St Thomas Aquinas, is set as the plainchant antiphon in the second Vespers of Corpus Christi, and meditates on the mystery of the Eucharist:

O sacred banquet, in which Christ is taken up; the memorial of His passion is cultivated; the mind is filled with grace; and the pledge of future glory is given to us. Alleluia.

Set in Messiaen’s golden-tinged multicolour F# major – the composer’s synaesthesia is a complex issue, but I think this description must suffice for now – the glorious nature of the Divine Worship encompassed by the source and summit sacrament of Christianity is reflected.

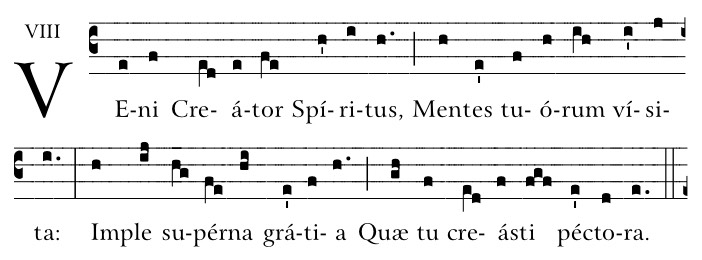

The technical difficulty for singers is mostly that when Messiaen indicates a tempo of lent he really means it; very few recordings are really slow enough to dwell in the harmonies and let them resonate around the sort of ecclesiastical building it is designed for. From the start, Messiaen also engages one of his favourite early techniques for destabilising any sense of a regular time signature: he extends the length of particular notes by adding the dot which indicates they are to be held for 1.5 times the normal duration. Thus, the phrases in the main theme begin with a dotted crotchet, continuing in straight crotchets until quavers introduce minims, conceived as an arsis–thesis moment.

Back in January I wrote a post about the same composer’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps, composed a few years later than this motet, but also showing a great awareness of the eschatological nature of liturgical time.

It seems to me that the strength of Messiaen’s meditation here on the Eucharist is related to this point; by constituting a sacred banquet rather than an ordinary meal, it takes us out of normal time; the eucharistic anamnesis reflected in the second phrase of the text in turn mystifies and extends our understanding of what it is for a once-for-all action to be present always and everywhere, yet still specific to a tangible location under the sacramental species. Messiaen’s harmonies go on to fill our minds with capacity to receive grace, and the consecrated elements themselves pledge to us the glory of Christ in so far as He dwells in us and we in Him.

Leave a comment