In 2003 the French and Lebanese organist and composer Naji Hakim wrote, to a commission of Leo Abbott of Boston, a former student of his, a piece in memoriam Theodore Marier, noted teacher and advocate for Gregorian plainchant. That inspiration, together with Hakim’s extensive practice as a liturgical improviser, leads to no surprise that the resulting work turns out to be based almost entirely on material derived from plainchant.

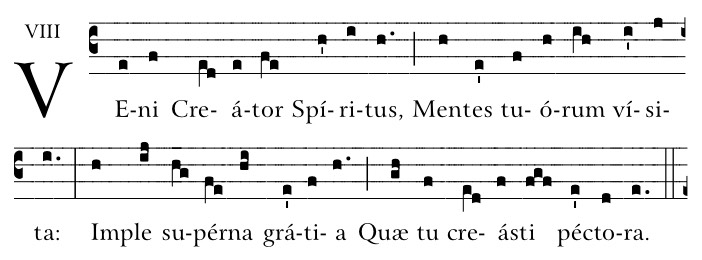

Specifically, Gregoriana draws on three chants, one taken from Marier’s edition of Hymns, Psalms and Spiritual Canticles, two from the Liber Usualis. The piece is audible sectional, with contrasts between arpeggiated flourishes, rhythmically-driven toccatas and melodic statements of harmonised chant material. Although all material can be seen to be derived from the three chants, they are not always in the melodic foreground to the listener. The overall effect of hearing the piece is very similar to listening to an organist improvise on the same themes; again, no surprise given Hakim’s experience and tendency.

Just a couple of years before writing this piece, Hakim had published something of a tirade against what he saw as a misinterpretation of the intentions of the Second Vatican Council with regard to music in the liturgy; it is his quotation of Pope John-Paul II on the subject which gives the title to this post. In the context of this communiqué, an unapologetically modernist work drawing extensively on plainchant remained a political and polemical choice.

While it seems there are questions of simple taste which need not have theological import, it is difficult to disagree that “At a time when Art is turning its back on spiritual values, one of the first concerns of the … church should be to open the door to artists, starting from within the liturgy, instead of either ignoring them or shutting them out completely.” Nor that “the lowest common denominator has become the rule, in order to allow the participation of the common people” and that this is not a necessary implication of the laudable intention that they be included. Indeed, our churches are often offensively patronising in what they assume the ‘common people’ might want, and risk thereby failing to offer them the rich wine of Christian and theological tradition, let alone artistic heritage, emptying the liturgy of its own value in doing so.

Is it too much to hope that musicians and artists will continue to find inspiration, as Hakim does, in plainchant and in the traditions of Christian liturgical music; to compose ground-breaking works which build on, rather than ignoring, that tradition? Can the leaders of our Churches open their minds to the possibility that even ‘ordinary’ members of the congregation could find therein something of value in their development in the faith, and that outsiders could hear something worth coming into Church for? Is it not in this sort of music that theology can indeed ‘express the mystery of faith’?

Leave a comment