In 1892 the director of the Paris Conservatoire is supposed to have said of a dangerously modern candidate for that institution’s professorship of composition ‘Never! If he’s appointed, I resign.’ In 1896 that same candidate took up the professorship under a different director, and in 1905 became director himself in turn.

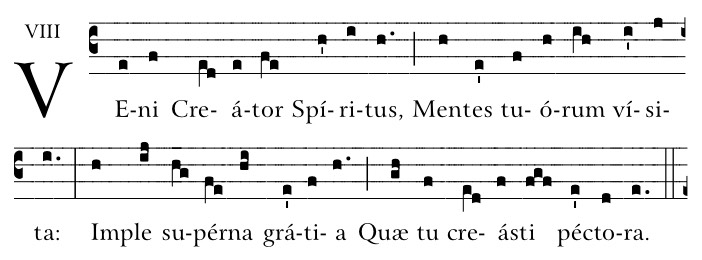

Many years before, while a nineteen-year-old student at the École Niedermeyer, the same man, Gabriel Fauré, had won first prize for a composition for voices accompanied by organ or piano, setting a text attributed (not necessarily accurately) to St Ambrose, in a paraphrased French version which had been made by the seventeenth-century playwright Jean Racine. It is not entirely clear why it is Racine’s name which gets the credit of being in the title of the song, which is known as the Cantique de Jean Racine.

A comparison of the Latin and French texts shows immediately that the latter is more florid and there is a certain elegance to it, which Fauré matches with long vocal phrases and a gentle, restrained, accompaniment:

Consors paterni luminis,

lux ipse lucis et dies,

noctem canendo rumpimus:

assiste postulantibus.

Aufer tenebras mentium,

fuga catervas daemonum,

expelle somnolentiam

ne pigritantes obruat.

Sic, Christe, nobis omnibus

indulgeas credentibus,

ut prosit exorantibus

quod praecinentes psallimus.

Verbe égal au Très-Haut, notre unique espérance,

Jour éternel de la terre et des cieux,

De la paisible nuit nous rompons le silence:

Divin Sauveur, jette sur nous les yeux.

Répands sur nous le feu de Ta grâce puissante;

Que tout l’enfer fuie au son de Ta voix;

Dissipe le sommeil d’une âme languissante

Qui la conduit à l’oubli de Tes lois!

Ô Christ! sois favorable à ce peuple fidèle,

Pour Te bénir maintenant rassemblé;

Reçois les chants qu’il offre à Ta gloire immortelle,

Et de Tes dons qu’il retourne comblé.

Translation has been subject to posts here before, and it is hard to see how the effect of Fauré’s Cantique could have been achieved with the shorter phrases of the Latin from the breviary (Tuesday Matins). And, though a work of youth, similarities with the same composer’s later Requiem are often heard – a work in which he did set texts in Latin.

Other liberties in translation may also have theological import: ‘Ambrose’ signals the partnership in light of Christ, addressee of the hymn, with the Father, Racine brings in the reference to John’s prologue by addressing the Cantique to the ‘Word equal to the most high’ and although the music is certainly luminous, the French ‘jour’ is only one syllable.

I find that sort of detail interesting, but perhaps it would be more judicious to end rather closer to the main point of the song as a whole: that the presence of God is what renders our worship fruitful; that when the people of God gather, grace is offered, those parts of ourselves which we know to be dark can be enlightened, and we can be filled with His gifts.

Leave a comment